Exercise 1: The Impact of Citizen Journalism

1. Find some examples of news stories where ‘citizen journalism’ has exposed or highlighted abuses of power.

2. How do these pictures affect the story, if at all? Are these pictures objective? Can pictures ever be objective?

3. Write a list of the arguments for and against. For example, you might argue that these pictures do have a degree of objectivity because the photographer (presumably) didn’t have time to ‘pose’ the subjects, or perhaps even to think about which viewpoint to adopt. On the other hand, the images we see in newspapers may be selected from a series of images and how can we know the factors that determined the choice of final image?

4. Think about objectivity in documentary photography and make some notes in your learning log before reading further.

“Citizen journalism, also known as collaborative media, participatory journalism, democratic journalism, guerrilla journalism or street journalism, is based upon public citizens “playing an active role in the process of collecting, reporting, analyzing, and disseminating news and information.”[5] Similarly, Courtney C. Radsch defines citizen journalism “as an alternative and activist form of news gathering and reporting that functions outside mainstream media institutions, often as a response to shortcomings in the professional journalistic field, that uses similar journalistic practices but is driven by different objectives and ideals and relies on alternative sources of legitimacy than traditional or mainstream journalism”.Jay Rosen offers a simpler definition: “When the people formerly known as the audience employ the press tools they have in their possession to inform one another.” The underlying principle of citizen journalism is that ordinary people, not professional journalists, can be the main creators and distributors or news. Citizen journalism should not be confused with: community journalism or civic journalism, both of which are practiced by professional journalists; collaborative journalism, which is the practice of professional and non-professional journalists working together; and social journalism, which denotes a digital publication with a hybrid of professional and non-professional journalism” (wikipedia accessed 12/07/2021).

Some sources cite examples of citizen journalism going as far back as the birth of the United States. Dan Vaughan, writing in Britannica.com, talks about citizen journalism impacting public opinion “…activist patriots printed pamphlets explaining why they supported the colonies’ independence from Britain. One of the most famous and influential of those citizen journalists was Thomas Paine, whose roughly 50-page pamphlet Common Sense methodically outlined why the 13 colonies should overthrow British rule. Such publications went a long way toward informing public opinion” (britannica.com Accessed 01/08/2021). According to Micha Barban Dangerfield, the amateur film of President Kennedys assanation was a ‘proto-form’ of citizen journalism due to its ‘inexpert nature’ (https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/p/photojournalism/power-people – accessed 01/08/2021). However, it was the rise of mobile technology, handsets and social media, which really accelerated and gave citizen journalists a platform to broadcast and amplify their message globally.

The rise of citizen journalism is important on many levels including giving voice to marginalised communities-those that might fight for attention or be ignored in main-stream media e.g. LGBT in Russia, exposing abuses of power-e.g. riots in Minsk, Belarus, and giving an alternative view to established media bias of which a small minority control the majority of what we hear and see. Some notable examples include:

The arrest of Floyd George

An example of citizen journalism was the arrest and death of George Floyd. The police account and those of citizen journalist footage, specifically Darnella Frazier, a teenager from Minneapolis who recorded the incident and posted her video online differed on many points from the police account and was instrumental in convicting the policeman for his murder.

Police accounts state he resisted arrest but footage from Frazier’s video show this was not the case and the subsequent treatment of Mr Floyd-a police officer kneeling on his neck while he pleaded that he could not breathe, led to his death. Despite Police claims that they did everything within the law, the use of citizen journalist footage helped raise awareness of police arrest methods, the obvious brutality and subsequent convistion.

Ian Tomlinson

Ian Tomlinson was a newspaper vendor making his way home through a demonstration when he was hit by police on the leg and pushed to the ground who then suffered a heart attack shortly afterwards. Police accounts of the incident were different from citizen journalist footage that emerged days later exposing how he was roughly treated. Subsequently, an inquest jury returned a verdict of unlawful killing, and the police offer responsible, Simon Harwood, was prosecuted for manslaughter. Although found not guilty, he was discharged from the police force and after a civil lawsuit, the Metropolitan Police Service settled with Ian Tomlinson’s family acknowledging that Harwood’s actions had caused Tomlinson’s death.

George Floyd Arrest

In both cases above images and footage have helped tell a different story than that offered by the authorities in question. The images have been taken as the events unfolded-for example in the case of Ian Tomilnson there is a bit of luck that the incident was captured on video and one could argue that the owner of the footage had little or no time to be objective or subjective one way or another. The image stills simply speak for themselves (for this viewer anyway).

In the case of Floyd George, the footage has helped build (and collaborate) an alternative account than the ‘official’ account offered by the police. People who were there gave statements and the images support their accounts as did footage from a surveillance camera-which would offer a machine-like objectivity.

Taking, making, looking at, and using photographs, all have a degree of subjectivity attached to them. We all have unique life experiences, upbringings, values and mental states. However, a degree of objectivity lends photographs authority but the medium is open to both interpretation,manipulation and abuse. Some of the arguments for and against include:

| For | Against |

| Democratises news coverage. Everyone is a potential witness of an event or happening and has the means to report on it and broadcast that report.

The raw nature of images/footage can lend authenticity Can help highlight issues not covered by mainstream journalism e.g. Israeli evictions of Palestinians. Helps highlight issues and alternative views to those of state-run (or highly regulated) media e.g China-authorities in Wuhan (source of COVID outbreak), arrested a lawyer and citizen journalist Chen Qiushi for reporting on the coronavirus situation and publishing her views and images on social media. Another, Fang Bin, a Wuhan businessman who posted videos filming city hospitals, was taken into custody by authorities two days later. Their accounts were very different from the authorities. Gives people an alternative take on events often helping catch wrong-doing. Gives local events a voice. Can help and inform and provide embedded coverage when events are breaking e.g. 10/11, the tsunami that devastated Banda Aceh, Indonesia, in 2004, Arab spring demonstrations, demonstrations and state response (brutal) Minsk, Belarus 2020. Can help supplement professional journalism.

|

Anyone can be a reporter regardless of skill or education. This raises quality and objectivity concerns.

Photographs can be easily decontextualised and dislocated (applies to all photos regardless of source) if not presented with proper narrative and intention. Can be overly biased and sway public opinion negatively. Social media platforms give everyone an ‘open mic’ to air (and amplify) their views .e.g. fake news A lack of impartiality, fact-checking etc can lead to a lynch mob mentality. Mainstream journalists have more rights to cover events (and corresponding infrastructure to support -editors and lawyers to fact check and recourse to legal help if abused) whereas citizen journalists can risk harassment and even violence. Inaccurate and improperly researched news reports of poor quality which create ‘news noise’. The full impact and power of social media platforms not fully understood-many open to abuse which makes it too easy to disseminate ‘fake news’ e.g Russian interference in US elections centred on fake news via social media. Regardless of the shortcomings of established media outlets (and their obvious agendas and political leanings) they do provide a level of professional standards for journalists to follow. Citizen journalists do not have to adhere to these standards.

|

Objectivity in documentary photography

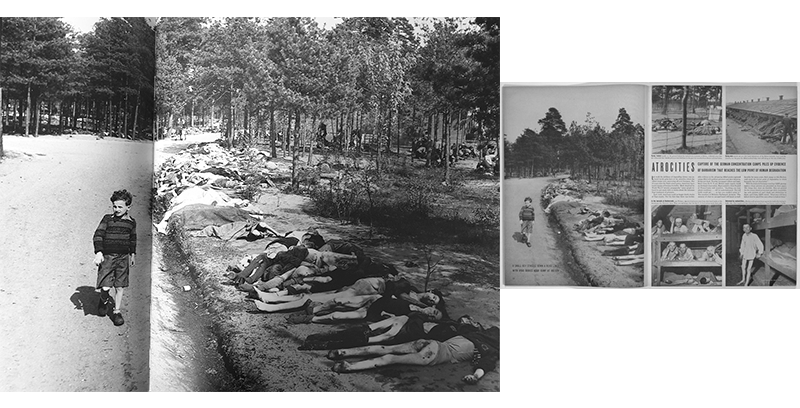

For me, at this point in time, the concept of objectivity in photography involves the taker, the viewer and user of the photographs. A photographer may objectively (as is possible) take a photograph of a particular scene but that photograph could be used in a much different context by an editor of a magazine. Take for example the photographs of the nazi concentration camps that appeared in Life magazine’s ‘Atrocities’ edition on May 17th 1945. One of the photos is of a boy walking alongside mounds of bodies with the caption ‘A Small Boy Strolls Down a road lined with Dead Bodies Near Camp at Belsen’. It leaves the nationality of the boy open. In fact, the boy was a Belgian Jew. A survivor. The assumed identity of the boy shifts the meaning of the photograph completely. If he was understood to be German, then it can be read as a metaphor for the German ambivalence (a notion that Life was pushing in its editorials) towards the nazi atrocities. The photograph was also heavily cropped along the right-hand side changing its meaning and context. In the original there is more focus on the bodies to the right-the eye is pulled into the photo from that point and the significance of the boy diminishes. The cropping of the photograph, the lack of editorial to make clear that the boy is Jewish and a survivor, raises questions around the objective use of the photograph. Had Life some other agenda at play?

Photographs leave us with a record of what was captured within the frame, a sliver of time captured. However, how that photograph is presented to a viewer changes its meaning. If it’s hung in a gallery, this lends it kudos and importance, if it is part of an editorial piece in a newspaper, this can also change its meaning no matter the intention of the photographer.

During the miner’s strike s of 1984-85 many of the photographs and media coverage were taken from behind the police cordon (Arthur Scargill / NUM didn’t trust the press and didn’t co-operate or interface with them effectively -Scargill saw them as an  enemy). As a result, many of the stories and imagery from the strike show the miners attacking the police and this helped shape public opinion against them. Additionally, the right-leaning press used and misinterpreted photos of Scargill-a famous one being when he was waving to strikers and the Sun newspaper used it as a comparison to the nazi salute.

enemy). As a result, many of the stories and imagery from the strike show the miners attacking the police and this helped shape public opinion against them. Additionally, the right-leaning press used and misinterpreted photos of Scargill-a famous one being when he was waving to strikers and the Sun newspaper used it as a comparison to the nazi salute.

Pure objectivity in photography is well suited to science and medicine etc. here what is recorded is often the difference between life and death. Recently I saw a documentary about the new nuclear power station being built in Hinkley Point. During the construction of the reactor walls the engineers needed the cement mix to be of a certain quality, tolerance and solidity. They used X-rays and photos of them to determine if the wall was sealed. The photographs were taken as part of the ultimate objective truth.

Some early practitioners of documentary photography:

Eugène Atget, (1857-1927) documented life and buildings in ‘old Paris’ and is regarded a pioneer of documentary photography. His compositions are records of places rather than subjective rather than artistic compositions-“For more than 20 years by my own work and personal initiative I have gathered from all the old streets of Vieux Paris the old hôtels, historic or curious houses, beautiful facades, beautiful doors, beautiful woodwork, door knockers, old fountains,” he once said. (http://www.artnet.com/artists/eug%C3%A8ne-atget/ accessed 02/08/2021).

Walker Evans (1903-1975) Evans recorded the American way of life- street scenes, everyday life, as well as documenting the Great Depression. “I used to try to figure out precisely what I was seeing all the time, until I discovered I didn’t need to,” he once explained. “If the thing is there, why, there it is.”

George Rodger(1908–1995) George Rodger was a British photojournalist noted for his work in Africa and for photographing the mass deaths at Bergen-Belsen concentration camp at the end of the Second World War.His photographs of the survivors and piles of corpses were published in Life and Time magazines and were highly influential in showing the reality of the death camps. Rodger later recalled how, after spending several hours at the camp, he was appalled to realise that he had spent most of the time looking for graphically pleasing compositions of the piles of bodies lying among the trees and buildings. This traumatic experience led Rodger to conclude that he could not work as a war correspondent again. Leaving Life, he travelled throughout Africa and the Middle East, continuing to document these areas’ wildlife and peoples.(Wikipediaaccessed 27/11/2021)

Do you think Martha Rosler is unfair on socially driven photographers like Lewis Hine? Is there a sense in which work like this is exploitative or patronising? Does this matter if someone benefits in the long run? Can photography change situations?

● Do you think images of war are necessary to provoke change? Do you agree with Sontag’s earlier view that horrific images of war numb viewers’ responses? Read your answer again when you’ve read the next section on aftermath photography and note whether your view has changed.

● Do you need to be an insider in order to produce a successful documentary project?

References

Having read Martha Rosler’s article ‘In, around, and afterthoughts (on documentary photography 1981)’, I’ve come to the conclusion that there is much more to consider when evaluating documentary photography including the photos of Lewis Hine. It appears that Hine had best intentions when taking and publicising his photographs but if you consider the wider eco-system within which they exist, you have to say that Rosler make a strong case no matter how inconvenient and unpalatable that may be.

While reading her article I was reminded of a point made in ‘Decolonising the camera,Photography in Racial Time’ about George Rodger’s photographs of Belsen and their use in Life magazine in august 1945. The horror of the photographs try to speak for themselves but the narrative has a key role to play in describing the unspeakable horror- yet the images cant explain how we came to this point or why Life magazine choose to publish at this point in time and not earlier- photographs of the nazi camps had been circulating since 1942. The photographs don’t tell us that they were published against a backdrop of international anti-jewish sentiment that only changed once the horrors of the camps become known. So the images helped provoke change but they didn’t explain the context, as Sealy remarks ‘images that act as witness to atrocities need to be read as construction and distortions simultaneously’ (Sealy 2019 page 68).

A lot has changed since the hay-day of photo-journalism and the system (glossy magazines and books, news papers, up the chain into galleries all the while getting more expensive and creating reputations) that created heroes of its photographers that often becoming bigger than the stories they tried to tell ( Roslar cites examples of David Burnett’s photos from Santiago de Chile and Dorothea Lange’s Mother and Child-both photographers went on to fame and fortune while their subjects (victims?) lives didn’t change for the best). The key elements of Rosler’s arguments hold a lot of weight and some go to the heart of what a photograph is and is not. Because people generally accept a photograph as a document that tells the truth, it is open to manipulation and that works in many directions.I don’t feel a photograph on its own can change much although many have been part of the evidence that help solve crimes and convict criminals. What I appreciate about Rosler is that she pulls back the veneer of hypocrisy to expose the real issues and attempts to hold the discipline of documentary photography to account for exploiting the pain of others to build careers and uphold a system where many have skin in the game- (just today I got an email from Magnum offering photos of its alumni for $100 a pop).

I agree partly with Sontag’s oft quoted assertion that too many horrific images of war numb viewers’ responses-but thats the same of too much of anything and it’s a bit simplistic to draw that conclusion. Images are part of an eco-system and its how that eco-system to uses them often determines the outcome.

Being an insider can be both a help and hindrance. Sometimes you need distance but also having context can help as well. Empathy often needs to be developed through association even if it leads to a certain amount of bias.

References

Bernard, Bruce, Cartier-Bresson, Henri, 1994, Humanity and Inhumanity, The Photographic Journey of George Rodger, PhaidonVaughan,

Dan, Citizen Journalists, https://www.britannica.com/story/citizen-journalists

Dangerfield, Micha Barban, The rise and rise of Citizen Journalism, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/p/photojournalism/power-people-accessed 01/08/2021)

Seely, Mark, 2019 Decolonising the camera,Photography in Racial time, Lawrence & Wishart, London