Exercise 4: Shafran critique

Go to the artist’s website and look at the other images in Shafran’s series.

You may have noticed that Washing-up is the only piece of work in Part Three created by a man. It is also the only one with no human figures in it, although family members are referred to in the captions.

In what ways might a photographer’s gender contribute to the creation and reading of an image?

What does this series achieve by not including people?

Do you regard them as interesting ‘still life’ compositions?

Nigel Shafran (born 1964) is a photographer and artist. His work has been exhibited at Tate and the Victoria and Albert Museum. In the 1980s Shafran worked as a fashion photographer, before turning to fine art photography. Talking to The Guardian journalist Sarah Philips, Shafran described his work as, “a build-up of images, often in sequences. There is a connection between them all. Basically, I’m a one-trick pony: it’s all life and death and that’s it.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nigel Shafran accessed 21/03/2022)

In what ways might a photographer’s gender contribute to the creation and reading of an image?

My first reaction to this question was ‘none’ but on reflection gender of a photographer could open complex issues around intent and affect the way images are read. For example, the photographs of Sally Mann have caused a lot of debate around the nudity of children in her series that chronicles their everyday life and instances. In an article in the New York Times Richard B. Woodward comments,

‘The nudity of the children has caused problems for many publications, including this one. When The Wall Street Journal ran a photograph of then-4-year-old Virginia, it censored her eyes, breasts and genitals with black bars. Artforum, traditionally the most radical magazine in the New York art world, refused to publish a picture of a nude Jessie swinging on a hay hook. And Mann’s images of childhood injuries — Emmett with a nosebleed, Jessie with a swollen eye — have led some critics to challenge her right to record such scenes of distress. “It May Be Art, but What About the Kids?” said the headline in an angry review in The San Diego Tribune. Mann has so far been spared the litigation that surrounded the Robert Mapplethorpe shows. And unlike Jock Sturges, whose equipment and photographs of nude prepubescent girls were confiscated by the F.B.I., she has not been pursued by the Government on child pornography charges.

It could be argued that because she is a woman people see the photographs differently- as an expression of her love and care for her children rather than anything sinister or unsavoury. The fact that they were taken by a woman makes the nudity easier to accept and look at.

When creating images it could also be easier (opinion of 1 here) that it’s easier for women to approach strangers to participate in their projects. The work of Trish Morrissey comes to mind, especially her series ‘Front’ where she asked complete strangers, family groups if she could substitute one of them for herself and take a photograph of her in their stead as part of their family. For sure these types of situations depend on the personality of the photographer and how they ask subjects and approach the situation, it could be argued that a women might be seen as less ‘threatening’.

What does this series achieve by not including people?

Do you regard them as interesting ‘still life’ compositions?

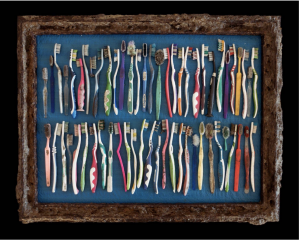

Every toothbrush belonged to a person-just like you.

By not including people we are presented with aspects of Shafran’s life (in this case his washing up habits or rituals) and we infer things about him as a person. We can see the type of pots he uses -standard ware as opposed to designer or expensive, he piles them up and leaves them to dry, he doesn’t seem to have a dishwasher and the kitchen space is small – all this presents evidence which we filter (through our own world view) to build a picture about him and his life. This is an interesting and alternative way of presenting clues about a person which might tell us more about them than say an enigmatic headshot.

I don’t see the images as still life compositions but rather clues about the person, a glimpse into their life with which I build a picture about them. Between the caption and the image, I build a portrait of the person.

I am also reminded of the series Dzhangal by Gideon Mendel an alternative portrait of asylum seekers in the Jungle refugee camp in Calais, France. Instead of presenting photographs of people (which he felt might be exploitative) he used images of everyday artefacts. These are especially powerful as the viewer is forced to humanise the residents of the camp through their banality of everyday life.

References

Woodward B Richard, 2015, The Disturbing Photography of Sally Mann (https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/19/magazine/the-disturbing-photography-of-sally-mann.html?searchResultPosition=4 accessed April 3rd 2022)

https://gideonmendel.com/dzhangal/ (accessed April 3rd 2022)