Exercise 1: Analysis

Exercise 1: Analysis

Analyse an image in your chosen genre.

Complete one genre analysis activity (Exercise 1) following the guidance in your chosen genre resource document:

- Thinking About Landscape (Exercise 1: Establishing Conventions)

- Still Life – The Objectness of Things (Exercise 1: Historic Still Lives)

- The Origins of Photographic Portraiture (Exercise 1: Historic Portrait)

- Documentary Traditions (Exercise 1: Humanism)

Analysis can take the form of a diagram, annotated notes, text, an A/V presentation, or voice memo. Post this to your learning log.

Do some research into historic photographic portraiture. Select one portrait to really study in depth. Write a maximum of 500 words about this portrait, but don’t merely ‘describe’ what you see. The idea behind this exercise is to encourage you to be more reflective in your written work (see Introduction), which means trying to elaborate upon the feelings and emotions evoked whilst viewing an image, perhaps developing a more imaginative investment for the image.

To help with the writing, you might also want to use a model developed by Jo Spence and Rosy Martin in relation to helping dissect the image at a more forensic level, this includes:

The Physical Description: Consider the human subject within the photograph, then start with a forensic description, moving towards taking up the position of the sitter. Visualise yourself as the sitter in order to bring out the feelings associated with the photograph.

The Context of Production: Consider the photographs context in terms of when, where, how, by whom and why the photograph was taken.

The Context of Convention: Place the photograph into context in terms of the technologies used, aesthetics employed, photographic conventions used.

The Currency: Consider the photographs currency within its context of reception, who or what was the photograph made for? Who owns it now and where is it kept? Who saw it then and who sees it now?

Post your thoughts in your learning log or blog.

I did this exercise for the course Identity and Place, but a visit to the exhibition You Name It has prompted me to revisit it as the image I originally did the analysis on has had a new lease of life thanks to the work of Sasha Huber, a Swiss-Haitian artist.

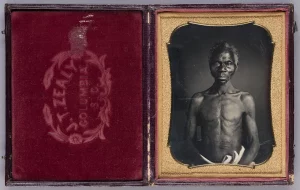

In 1976, 15 portraits of enslaved people were found in an attic of the Harvard Peabody Museum. They were taken by the photographer Joseph T Zealy in South Carolina in 1850, having been commissioned by Harvard scientist Louis Agassiz, to ‘prove’ his theory of polygenism – a racist theory that different peoples -European and African- came from different species, using skin colour and physiognomy as evidence and proof that white people were the superior race.

In 1976, 15 portraits of enslaved people were found in an attic of the Harvard Peabody Museum. They were taken by the photographer Joseph T Zealy in South Carolina in 1850, having been commissioned by Harvard scientist Louis Agassiz, to ‘prove’ his theory of polygenism – a racist theory that different peoples -European and African- came from different species, using skin colour and physiognomy as evidence and proof that white people were the superior race.

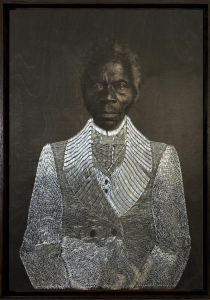

One of the Zealy images was of a man called Renty, and Huber, in her exhibition “You Name It”, used her staple-gun method to update the images in garments fashioned on clothes of well-known abolitionists. When I heard about the exhibition, I was initially sceptical as I thought that the people in the images, already the centre of a court case between Harvard and a living relative of Renty, would never be free. Their images were taken forcibly when they were enslaved, and now someone wanted to dress them up and call it art-this how my thinking initially went. However, I was quite moved once I saw the large life-size images up close. The exhibition’s context ( have locations named after Louis Agassiz- including a crater on the moon- changed) and the artist’s treatment completely transformed and humanised the images. They gave them a sense of dignity, and self, something Zealy and Agassiz had blatantly taken from the sitters of the original images.

Huber used mixed media to breathe new life into the portrait of Renty, using her staple gun method to recreate clothes worn by the abolutionists.

The Context of Production: The ‘new’ image of Renty overlaps portraiture and art. The use of the staple gun has helped resituate the image in the here and now. Huber’s exhibition highlighted the wrongs of the past, putting the sitters in a new context.

The Context of Convention: The initial images were daguerreotypes, taken in a dispassionate way to catalogue people without any regard or respect for their humanity. They sitters were a commodity and did what they were told. However, in the new context, and with the coat covering Renty’s nakedness and restoring his humanity (somewhat), we are left with his gaze, and it is this that holds us transfixed. For me, his dignity is now amplified. One is forced to view the man as an individual and not as part of a collective known as ‘enslaved people’. The new treatment goes someway to deliverting what we would expect from a portrait.

The Currency: This is the most contentious aspect of the Zealy Photographs. Initially forcibly taken by people who considered the sitters as property, Harvard found the images and claimed them as its property, despite a claim by a living relative. This opens up the issues about ownership and where and when the images should be viewed.

References

Barbash,Ilisa, Rogers Molly and Willis,Deborah,(2020), To Make Their Own Way in the World: The Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerreotypes,New York,Peabody Museum Press/Aperture

Clarke,Graham,1997, The Photograph,New York,Oxford University Press

Segal, Parul, (Sept 29th 2020) The First Photos of Enslaved People Raise Many Questions About the Ethics of Viewing, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/29/books/to-make-their-own-way-in-world-zealy-daguerreotypes.html (accessed March 2023)