Imaginative Spaces (Project 2 Lens Work)

Research point

‘I’m inclined to think that there is no such thing as a photojournalistic image, only a photojournalistic use of an image.’

(David Campany)Read around the photographers above and try to track down some of the quotations, either in the course reader (Liz Wells) or online. Write up your research in your learning log.

Now look back at your personal archive of photography and try to find a photograph to illustrate one of the aesthetic codes discussed in Project 2. Whether or not you had a similar idea when you took the photograph isn’t important; find a photo with a depth of field that ‘fits’ the code you’ve selected. Add a playful word or title that ‘anchors’ the new meaning.

The ability of photographs to adapt to a range of usages is something we’ll return to later in the course.

The research exercise brought home to me the breadth and depth of photographic debate and scope. Tracking down the quotations is like peeling back layer after layer that can take you in many different directions, but you have to start somewhere, and as I researched the quotes and photographers, their take on photographic approaches, their movement affiliations (I found 144 different photography movements https://www.theartstory.org/movements/photography-focused/), I began to get a flavor (and appreciation) for the diversity of approaches.

The exercises in ‘Imaginative spaces’ also forced me to slow down and consider aperture and focal length and their influence on my photographic output.

Shallow or deep focus can influence how a photograph is read and this can be used by photographers to covey a message, direct the eye, and coupled with other elements of composition, point, line, frame, etc, give the photographer a creative pallet of choices that can be used creatively and intentionally when taking a photograph, to determine a specific outcome.

“Deep focus gives the eye autonomy to roam over the picture space so that the viewer is at least given the opportunity to edit the scene himself, to select the aspects of it to which he will attend”. (Bazin (1948) quoted in Thompson & Bordwell, 2007

‘The most political decision you make is where you direct people’s eyes.’ (Wim Wenders (1997) quoted in Broomberg & Chanarin, 2008)

Below are some photographers who have employed deep and shallow focus to affect a specific outcome:

Fay Godwin

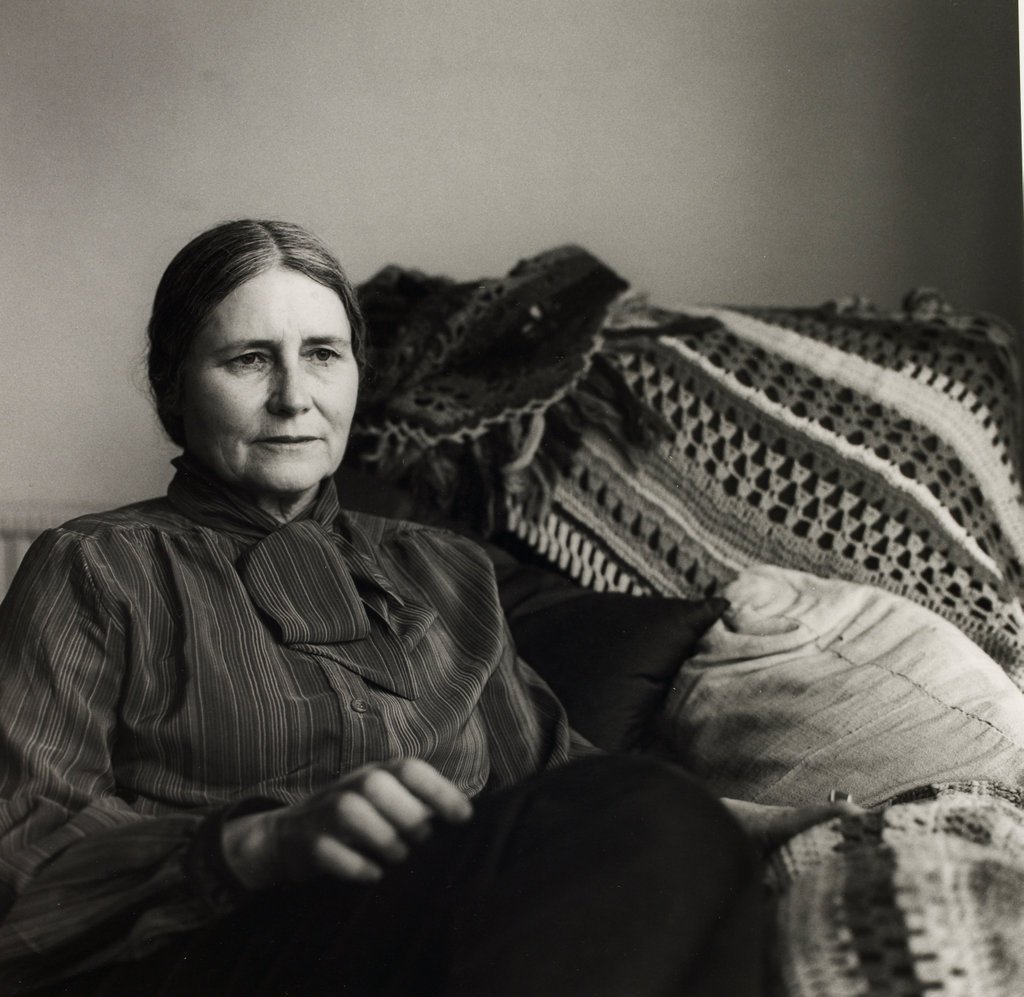

Fay Godwin was a renowned British photographer known for her landscape photography and portraits of famous literary figures.

Godwin was president of the Ramblers Association from 1987 to 1990 and a passionate environmentalist. She used her photographs to draw attention to environmental issues and campaigned for open access to the countryside. Her book ‘Forbidden Land’ a critique on land access issues is credited in helping change the law for rambler rights and access.

As a landscape photographer, Godwin made good use of deep focus and other (classic) elements of composition:

Her use of line, light and shade, and direction were classic rather than innovative. In Path and Reservoir above Lumbutts, Yorkshire (1977), the path leads the eye into the picture from the bottom left, a stone wall picks up the path and leads to the reservoir. Careful technical control ensures that the reservoir is highlit, the path and surrounding grass are of medium tone, present but not overwhelming. The surrounding hills are dark, as is the sky, save for a sunburst on the horizon. It is as mature a piece of photographic art as one could wish, Godwin at her most accomplished. The Guardian, Tuesday May 31, 2005 by Ian Jeffrey

Fences, Park, Lewis 1981

Godwin started out by doing portraits of a ‘who’s who’ of literary figures. Her style of portraiture was to use natural light and elements of the subject’s personal environment, her placing of subjects tends to be either left or right of the screen and the subjects come across as relaxed and conversational.

Gianluca Cosci

In his series, Panem Et Circenses, Italian photographer/artist Gianluca Cosci makes use of shallow focus and unusual points of view thus guiding the viewer’s eye to a specific point in his photos. Like Fay Godwin, Cosci uses photography to communicate political ideas and messages. In an interview with Kev Byrne he explains:

By the way, my series Panem et Circenses was taken exclusively around the Millennium Dome which at that time was a depressing no man’s land after being open for only 12 months in 2000. It was Blair’s vanity project to boost his image as “presidential” prime minister. That white elephant with a price tag of nearly one billion pounds of tax payers’ money was standing empty while he was declaring war against Iraq. I had the need to work on that specific place in that moment.

In another series- ‘Walls’- Cosci continues his theme of corporate power and zooms in on (corporate) buildings giving them an abstract feel, full of lines and symmetry, and a somewhat soulless feeling. I found I could relate to, and understand this series much easier than ‘Panem Et Circenses’ as the communication and metaphorical load was more direct, Cosci himself explains:

Standardisation is a tool of control and constraint of people into reassuring and harmless psychological and architectural boxes in which any hint of improbable rebellion would be easily sedated. My work tries to suggest these ideas showing sanitised office blocks, censored landscapes and lifeless environments. With my photographs, I would like to insinuate a subtle sense of violence in our deeply hierarchical society.

The final series of photos that caught my eye was ‘Oude meesters Series’ which Cosci describes as:

In museums, one’s behaviour is prescribed, controlled and monitored. One is supposed to use the space according to its strict purpose.

This is not a space for destabilization or rebellion, and personal freedom is reduced to basic acts, like an angry gaze, a rebellious glance or a silent hostility: minimalist subversion, micro institutional critique. Gianluca Cosci, 2018

Looking at Cosci’s work has given me a better understanding of how photographs work together in a series. In some instances e.g. ‘Walls’ the themes are less ambiguous than others -Panem Et Circenses, but all have a coherence that pulls you in to decipher whats going on.

Group F/64

Founded by 11 prominent photographers Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham, John Paul Edwards, Preston Holder, Consuelo Kanaga, Alma Lavenson, Sonya Noskowiak, Henry Swift, Willard Van Dyke, Brett Weston, and Edward Weston, ‘the name referred to the smallest aperture available in large-format view cameras at the time and it signaled the group’s conviction that photographs should celebrate rather than disguise the medium’s unrivaled capacity to present the world “as it is.” As Edward Weston phrased it, “The camera should be used for a recording of life, for rendering the very substance and quintessence of the thing itself, whether it be polished steel or palpitating flesh…The group’s effort to present the camera’s “vision” as clearly as possible included advocating the use of aperture f/64 in order to provide the greatest depth of field, thus allowing for the largest percentage of the picture to be in sharp focus” -Metropolitan Museum of Art (https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/f64/hd_f64.htm)

According to an entry in TheArtstory.org ( https://www.theartstory.org/movement/group-f64/) ‘One of the most famous photographic collectives in history, Group f/64 mounted a revolt against the dominant fashion within the art of photography which was to ape the painterly and graphic techniques associated with Bay Area Pictorialism. The members’ preference was for a style of art photography that would fully promote the camera’s unique mechanical qualities. As the Group declared in its 1932 manifesto: “Pure photography is defined as possessing no qualities of technique, composition or idea, derivative of any other art form [and] The Group will show no work at any time that does not conform to its standards.” Indeed, the diaphragm number f/64 from which the Group took its name, is the smallest camera lens aperture possible and thereby lends the image a sharpness and detail in depth that simply could not be replicated by the hand or in real time. The Group used large format view cameras to achieve their effect and they produced images ranging in theme through landscapes, still lifes, nudes, and architectural features.

Pictorialism (lifted from https://www.theartstory.org/movement/pictorialism/)

Pictorialists took the medium of photography and reinvented it as an art form, placing beauty, tonality, and composition above creating an accurate visual record. Through their creations, the movement strove to elevate photography to the same level as painting and have it recognized as such by galleries and other artistic institutions. Photography was invented in the late 1830s and was initially considered to be a way in which to produce purely scientific and representational images. This began to change from the 1850s when advocates such as the English painter William John Newton suggested that photography could also be artistic.

Although it can be traced back to these early ideas, the Pictorialist movement was at its most active between 1885 and 1915 and during its heyday it had an international reach with centers in England, France, and the USA. Proponents used a range of darkroom techniques to produce images that allowed them to express their creativity, utilizing it to tell stories, replicate mythological or biblical scenes, and to produce dream-like landscapes. There is no straightforward definition of what a Pictorialist photograph is, but it is usually taken to mean an image that has been manipulated in some way to increase its artistic impact. Common themes within the style are the use of soft focus, color tinting, and visible manipulation such as composite images or the addition of brushstrokes.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Pictorialism was closely linked to prevailing artistic movements, as the photographers took inspiration from popular art, adopting its styles and ideas to demonstrate parity between it and photography. Movements that were particularly influential were Tonalism, Impressionism and, in some instances, Victorian genre painting.

- Pictorialists were the first to present the case for photography to be classed as art and in doing so they initiated a discussion about the artistic value of photography as well as a debate about the social role of photographic manipulation. Both of these matters are still contested today and they have been made ever more relevant in the last decades through the increasing use of Photoshop in advertising and on social media.

- The movement led to great innovation in the field of photography with a number of the photographers associated with it responsible for developing new techniques to further their artistic vision. This laid the foundations for later advances in color photography and other technical processes.

Photograph neutrality and photograph as truth

Having begun my research into the different and creative ways one can use a lens coupled with aperture etc, led me to questions around photographic neutrality and a viewer’s natural disposition towards a photograph i.e. do viewers believe what they see? or mistrust it? is an interesting and complex one.

I’m reminded of the housing market, and how properties for rent are communicated using photographs. In the photo below a wide-angle lens with a short focal length was used to exaggerate (most likely or was a consequence of) the size of the property, this is common practice and ‘distorts’ the true representation of the property size. In this example and within its context, it is’delivering a neutral vision as an optical truth’-it is (most likely) a faithful representation of a 15mm lens on some camera or another, and the photograph will most likely be believed as a form of truth. Y0u just might be disappointed when you see the apartment in ‘reality’.

I’m reminded of the housing market, and how properties for rent are communicated using photographs. In the photo below a wide-angle lens with a short focal length was used to exaggerate (most likely or was a consequence of) the size of the property, this is common practice and ‘distorts’ the true representation of the property size. In this example and within its context, it is’delivering a neutral vision as an optical truth’-it is (most likely) a faithful representation of a 15mm lens on some camera or another, and the photograph will most likely be believed as a form of truth. Y0u just might be disappointed when you see the apartment in ‘reality’.

Gianluca Cosci offered his opinion in an interview when he opined,

Firstly, can we ever be sure of anything we see, even without a camera? That’s a profound and massive question that we will be asking for quite some time.

Secondly, the mind has a funny way of piecing things together to create some sort of homogeneity – not always so trustworthy and definitely not infallible, don’t you think? You know that saying: seeing is believing? It should be believing is seeing! As if all our complex neurological processes that give us what we perceive as perception can be reduced to something so black and white as that saying, but still, it’s very true sometimes.

Yes, painting, due to its texture, physicality, and possibly its clearly artificial, less faithful representation of reality make it seems less real. Photography, on the other hand, appears to “capture” reality, or better: capture a subjective reality, or arguably even time itself (or at least a fleeting glimpse of it), don’t you think?

Doing some desktop research I came upon this quote from an article ‘Responsibility and Truth in Photography’ (Jörg M. Colberg https://cphmag.com/responsibility_truth/) ‘Photographs don’t lie. To say a photograph lies is to believe that there can be such a thing as an objectively truthful photograph. There can never be. All photographs present a truth: their makers’.

While Wim Wenders positions depth of field as a political decision- ‘The most political decision you make is where you direct people’s eyes.’

(Wim Wenders (1997) quoted in Broomberg & Chanarin, 2008)-meaning where you direct people’s eyes can have an influence on how a photograph is read thus altering its ‘neutrality’.

Now look back at your personal archive of photography and try to find a photograph to illustrate one of the aesthetic codes discussed in Project 2. Whether or not you had a similar idea when you took the photograph isn’t important; find a photo with a depth of field that ‘fits’ the code you’ve selected. Add a playful word or title that ‘anchors’ the new meaning.