Exercise 1: Historic portrait

Do some research into historic photographic portraiture. Select one portrait to really study in depth. Write a maximum of 500 words about this portrait, but don’t merely ‘describe’ what you see. The idea behind this exercise is to encourage you to be more reflective in your written work (see Introduction), which means trying to elaborate upon the feelings and emotions evoked whilst viewing an image, perhaps developing a more imaginative investment for the image.

To help with the writing, you might also want to use a model developed by Jo Spence and Rosy Martin in relation to helping dissect the image at a more forensic level, this includes:

The Physical Description: Consider the human subject within the photograph, then start with a forensic description, moving towards taking up the position of the sitter. Visualise yourself as the sitter in order to bring out the feelings associated with the photograph.

The Context of Production: Consider the photographs context in terms of when, where, how, by whom and why the photograph was taken.

The Context of Convention: Place the photograph into context in terms of the technologies used, aesthetics employed, photographic conventions used.

The Currency: Consider the photographs currency within its context of reception, who or what was the photograph made for? Who owns it now and where is it kept? Who saw it then and who sees it now?

Post your thoughts in your learning log or blog.

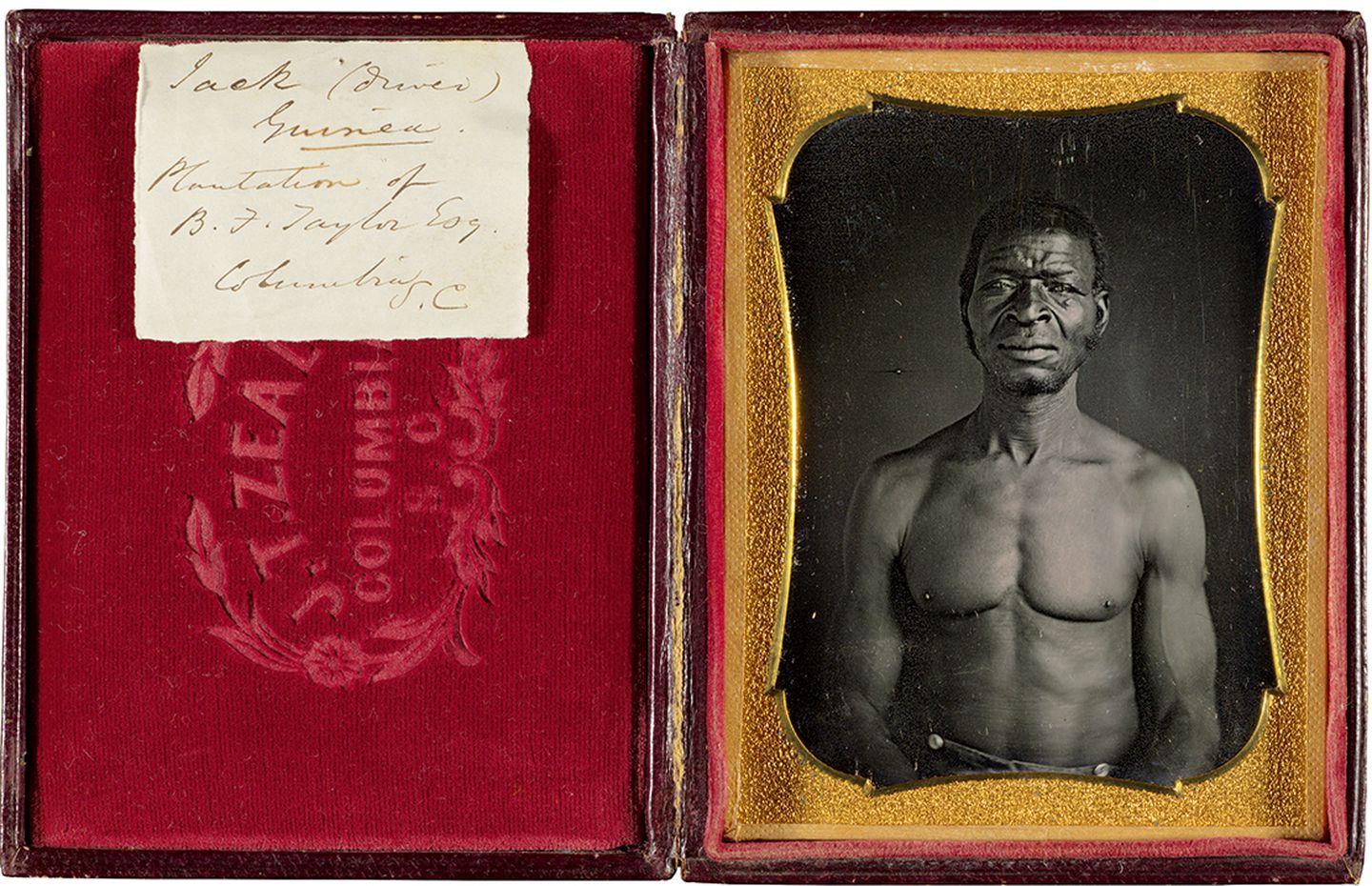

J. T. Zealy, Jack (driver), Guinea, Planation of B.F. Taylor, Esq., Columbia, S.C., March 1850 |

In 1976 15 portraits of enslaved people were found in an attic of the Harvard Peabody museum. They were taken by the photographer Joseph T Zealy in south Carolina in 1850, having been commissioned by Harvard scientist Louis Agassiz, an exponent of polygenism – a discredited (and racist) theory that different peoples -European and African- came from different species using skin colour and physiognomy as evidence and proof. The photographs are daguerreotypes, contain incredible detail, and show the sitters both from the side and front, stripped.

I have chosen one from the fifteen, a frontal half-body image of a man called Jack. This is no conventional portrait. Jack is stripped to be catalogued and used for some perverse comparative analysis. There are no backdrops typical of the time, or props, and Jack would have to remain still for a period of time while the daguerreotype exposed the image-about a minute. The image serves to locate an enslaved human being in the here and now. It is no longer a historical construct but a real person. We are given some details about him, his name, occupation, and his captor. He is no longer totally anonymous.

It’s difficult to speculate what was going through the photographer’s mind when he took the images-did he approach them with an air of scientific detachment? As a product of his time and place, did he de-humanise Jack and take the photographs with an air of superiority? I’m reminded of the photographer George Rodgers who photographed the aftermath of the Belsen concentration camp. Talking about his experiences, he explained,

‘It wasn’t a matter of what I was photographing, as what had happened to me in the process. When I discovered that I could look at the horror of Belsen, 4000 dead and starving lying around, and think only of a nice photographic composition, I know something had happened to me and had to stop. I felt I was like the people running the camp, it didn’t mean a thing (Rodger quoted in Shepard 2006 p. 102)’

I would like to think Zealy felt something on a human level; there is no doubt he applied his photographic expertise to produce the images, and when all the 15 images are looked together, one can’t help feeling he took them more in the spirit of cataloguing rather than with any artistic intent or that he even tried to get to know the people he photographed. In all probability, it was a paid assignment by a prominent scientist that may have helped him climb the social ladder of the time.

Looking at the image, I have mixed emotions, including unease, sadness and anger. Unease because I feel I’m intruding, participating, and complicit in Jack’s humiliation-his coercion, sadness at how millions of people were enslaved and could be reduced to mere commodities, and anger at the attempt to justify it with pseudo-scientific theories and the propagation of racial stereotypes. When I move beyond these, I see Jack. Looking slightly to the left (ordered to do so and not dare look his ‘master’ in the face?) I see sadness, pride and resignation on his face-maybe all 3 at the same time. I see his muscular body, and even though he has been stripped of many things, his humanity is coming through loud and clear. This helps situate Jack in the here and now-reaching out from the past to make his presence felt. And then his face, so expressive- something tells me it wouldn’t take much to make him smile-I say this more out of hope than reality-but who knows?

The discovery of the images has opened debates about ownership, context and use, perfectly summarised in a New York Times article,

‘Is there a correct way to regard these images? Should one view them, or any coerced image, at all? To whom do they belong? Do they quicken or numb the conscience? Does displaying them traumatize the living? Is it care or cowardice to keep them concealed? What do we owe the dead?’

The images have been exhibited widely, and a proven descendant of Renty (one of the images in the series) has come forwards and claimed ownership. These questions and issues are unresolved and will not go away.

I look at Jack’s image and can but reflect on how the very act of being photographed helped prove his existence, something his captors tried to deny him.

References

Barbash,Ilisa, Rogers Molly and Willis,Deborah, To Make Their Own Way in the World: The Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerreotypes,Peabody Museum Press/Aperture

Sehgal,Parul, The First Photos of Enslaved People Raise Many Questions About the Ethics of Viewing, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/29/books/to-make-their-own-way-in-world-zealy-daguerreotypes.html

http://historiccamera.com/cgi-bin/librarium2/pm.cgi?action=app_display&app=datasheet&app_id=3617 (Accessed 21/12/2022)